This is the second episode in a blogpost series chronicling my first experience in creating a student-centered learning environment. Click here to read Episode 1: Fear. Do we get a grade for this? As I walked to the blacktop to bring my students back to the classroom following break, I sensed their nervous excitement. I had flipped the model and put students in charge of their own learning and assessment. The students entered the classroom ready to barrage me with questions. The first question surprised me. “So, are you actually going to put this grade in the grade book? Like, officially?” I was asked.

“Of course,” I answered, “it is an assessment.” “But…it’s not a test,” the student answered, perplexed. This student had difficulty with the concept of non-traditional assessment. For all of his life, he had experienced assessments that had been created, administered, and scored by adults. And it was clear that the student believed the purpose of all these tests was for a grade in the grade book. The fact that I would give this control to him, that I would encourage him to take responsibility for his learning, was a foreign idea. “You decide your grade,” I said. I turned to the white board where I had written a make-shift rubric. Pointing to the rubric I said, “5 points per fact, 5 facts per category will result in 100%. Anything less than that, well…you can do the math and determine the grade you will get.”

The student who had asked about an official grade had grown up in a teacher directed environment of high-stakes testing, where he attributed the value of his self-worth as a learner to little more than numbers in a grade book. When adults attach more importance to grades than learning, when they focus on a single measure of proficiency rather than growth that can be demonstrated in multiple ways, they devalue the process of learning itself and squash students’ inherent curiosity and creativity. As I listened to the aforementioned student question me regarding grades, I was saddened. It is at that moment that I realized how detrimental a teacher directed model of instruction had been for my students. Students were coming to school not to learn, but to receive validation from a teacher. They came not to ask questions, but to answer them. It is a much higher cognitive task to generate a question than to answer one. Sadly, when students ask questions that do not quite align to a pre-made lesson plan, teachers may accuse them of being off-task, distracting the class, or showing disrespect.

Learning vs. Testing

A hand raised hesitantly. I called on the student who had raised her hand. “So, you are saying that as long as we follow that rubric we won’t have to take a test?” she asked. I answered her question with one of my own. “Are we here to take tests or to learn?” I asked. The room was silent. Students did not know how to react. Could it be that a teacher was suggesting that tests were not important? I continued, “A test is merely a method of showing what you have learned. Show me what you have learned, any way you choose, and you receive full credit. You may call it a test if you want, but it is simply proof of learning.”

At this point, I could have provided students with a choice board of options through which to demonstrate their understanding. However, I wanted to spark creativity in my students. I wanted to challenge them to come up with their own ideas. The unit on Ancient Egypt had just begun, and students would have weeks to ponder whether they wanted to take a teacher created assessment, or show their learning another way. I had planted a seed. I had begun to shift the ownership to students. And neither the students nor I truly knew what to expect.

Limitless Expression

As students progressed through the unit, I casually reminded them to think about ways they would prove their learning to me if they opted for a student created assessment. Not only did I restrain from providing a choice board, but I also did not provide exemplars from past classes. As this was my first attempt in flipping the model to student-led learning, I did not have any prior examples to provide. Students were bound only by a content-rich rubric. Students’ freedom in methods for expressing this content knowledge was limitless. In many classrooms, students are provided a choice board with options to show their knowledge (i.e., poster, video, drama, etc.) While this motivates students more than a teacher created assessment, limitless possibilities for demonstrating understanding focuses on content rather than a product, and inspires both critical thinking and creativity. Because I did not provide any options or prior examples, students did not focus on creating the best poster, or slide deck, or video. Rather, they led with the content and considered the most fitting method to demonstrate their learning.

How My Students Changed My Teaching

As I shifted the responsibility of assessment to my students, their engagement levels with the content rose dramatically and their creativity astounded me. The variety of methods students chose to demonstrate their learning truly inspired me to alter the way I ran my classroom. Rather than planning instruction of content, I began to design opportunities for students to explore content on their own, in accordance to their vision of how they would prove they had learned.

In the past, I had guided students through note-taking from information in the textbook, to ensure that they wrote down every fact and concept I believed was important. However, that model places the teacher as the one in control. Students’ only reason for writing down information was because it would be on the test. The focus was on testing, not on learning. In beginning the unit by providing a rubric first, and informing students that they would be responsible for proving their learning a few weeks later, I discovered that students were asking more questions regarding the content and took additional notes that I was not directing them to include. I began to focus on student learning rather than on my teaching. I continued to experiment. Could I trust my students to ascertain knowledge and concepts from the textbook with my explicit guidance? How would I differentiate for my struggling readers and English Learners if I did not guide them through each paragraph of the text? I decided to take a risk and see what my students would do. When I stopped teaching explicitly and gave students the freedom to learn independently, I discovered that students began teaching each other. Those with smartphones looked up vocabulary they did not know. Students began asking me questions instead of answering mine.

Validate Variability

In allowing my students limitless possibilities regarding their methods of proving their learning of content, I learned that each of my students was more creative and unique than I had ever realized. Each student, prior to beginning to demonstrate their content knowledge, was required to write an argumentative paragraph regarding how their method would prove their learning according to the rubric. I had a group of students ask if they could create a diorama. At first I thought this may not effectively allow them to show sufficient content knowledge. I indicated that the students would still need to include 5 facts about each of the 5 categories from the rubric. The students wrote about how a diorama would enable them to create a model of the geography of Ancient Egypt, complete with a scene of individuals from varying perspectives, clearly labeled with note cards to provide a more in depth analysis. Because I validated the students’ choice, they used creativity to develop a method for meeting all portions of the rubric. I would never have suggested a diorama on a choice board I had created for this unit; and yet, students found a way to make it work.

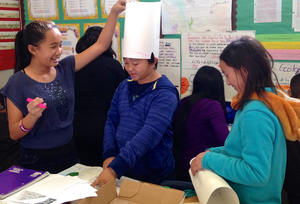

The variety of methods of demonstrating content knowledge was astounding. A group of students created a play, yet another group of students wrote a diary from the perspective of an Ancient Egyptian, and some students opted to create a mural of sorts on poster paper. As students owned this process of assessment, I discovered they displayed an unprecedented amount of motivation to continue their learning and add to their assessment deliverables. Students asked to come in during break, lunch, and beyond school hours to work on their assessment.

Little to No Tech? No Problem.

While we were very limited as to the technology in the classroom, I allowed a couple of students to use my teacher iPad. Another group of students used my teacher laptop. These students did not have these devices at home and had never created a multimedia presentation before. This was at a time when Google Classroom had not yet been invented. Students in our school used computing devices primarily for Accelerated Reader assessments. They had little to no other prior experience with this technology. And yet, these students discovered shortcuts for inserting pictures, learned how to share presentations and convert the format, and were primed to teach their peers once our 1:1 iPads arrived a few months later. I did not teach the tech. In fact, I had not explicitly taught content either, I simply designed learning opportunities and provided resources for students to learn on their own.

What Would This Look Like In Your Classroom?

Since this first experience in student created assessments, I have worked with many teachers who display nervous excitement about the possibility of trying this model in their own classroom. What would this look like with primary students, in a middle school mathematics class, or with students in a high school science class among others?